Christophe Lentschat oversees sales, development of new services, marketing and communication at European Fund Administration (EFA). In this capacity, he has a proven record in the acquisition of transfer agent (TA) clients and the creation of new TA services. In particular, he participated in the creation of EFA's TA Bureau service. Prior to joining EFA in 2000, Christophe was a management consultant with Deloitte Luxembourg. Christophe began his career with AXA Investment Managers Germany as a product manager. He holds a Master of Science degree from Sup de Co Reims, France, and a Master of Business Administration degree from Kellogg (Northwestern University), USA–WHU, Germany.

Abstract

Until relatively recently, transfer agent (TA) work was seen as a secondary activity in the fund accounting–custody chain. TA service providers typically earn relatively low fixed annual fees and a small charge per transaction. As such, they have suffered from a lack of investment in specific TA systems. This paper will examine how the most recent changes in product and distribution dynamics are creating new dynamics in the TA industry. It aims to assess the progress obtained in the automation of core TA functions and the existing potential for the development of new added-value TA services. It will attempt to answer the question of whether TA is still a necessary cost of doing business from a fund administrator and custodian perspective, or whether it is becoming a business line in its own right.

Keywords: transfer agent (TA), fund administration, specialised investment funds (SIFs), straight-through processing (STP), equalisation, dilution

Background

The transfer agent (TA) was formerly a function in the corner of the custody or fund administration department. The TA desk's work consisted of calculating trailer fees and other distributor remuneration (usually on a spreadsheet), based on a best-effort estimate of the investors' positions. Until recently, this paper would have made no sense: there were no TA service providers as such. The TA service provider as a separate enterprise or an independently managed profit centre is a new phenomenon, driven by regulation, and by increasing segregation and specialisation of the different elements of the funds services industry.

Most service providers in this industry earn a fee based on the funds assets. This applies to the manager, fund accountant, custodian and distributors. The TA service provider usually has the smallest cut - either a fixed annual fee, or fixed amount per account or transaction. This form of piecework remuneration reflects a persisting view that TA activities are a necessary cost in the distribution process, but with little to add to the performance of the fund. As such, TA service providers are usually mostly out of sight and out of mind of the investment managers and fund promoters - at least, until a large investor goes to them to complain.

In this environment, investment in automated solutions has been slow. Even in the larger service providers, fax and mail transactions are the most common form of transaction. Contrast this with the fund accountants automated processing of portfolio transaction using SWIFT, Bloomberg or proprietary interfaces to prime brokers and it is clear that TA service providers are some way behind the rest of the industry.

Funds are increasingly distributed through other investment vehicles. These ‘assemblers' include funds-of-funds, pension funds, unit-linked products and special purpose vehicles (SPVs). Compared to the traditional retail and institutional clients, these professional fund buyers have demanding requirements for rapid reporting, high levels of connectivity and customised reporting.

The Luxembourg Fund Industry

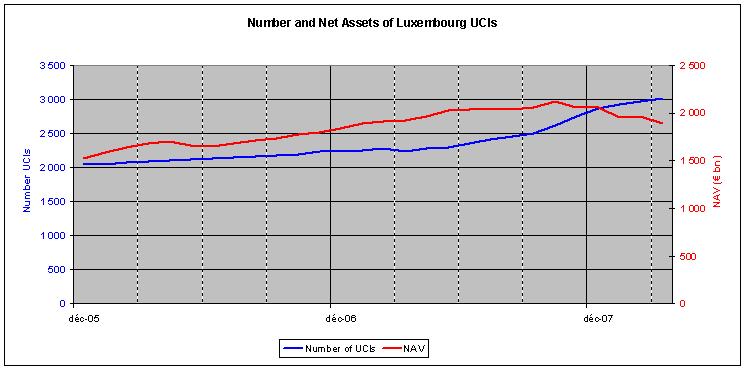

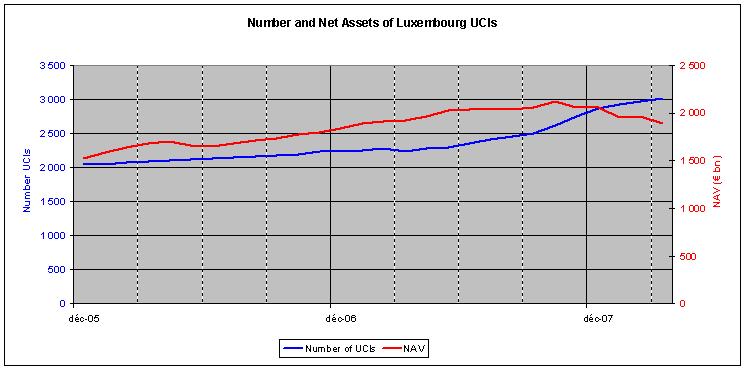

The Luxembourg fund industry has seen a decade of rapid growth. Recently, the number of funds has been growing at a rate of over 20 per cent per year.1

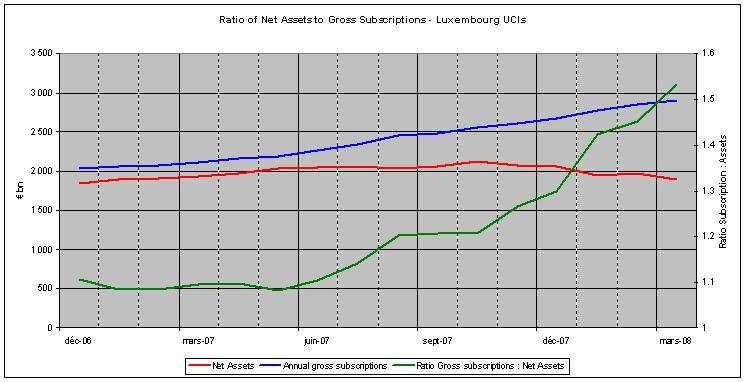

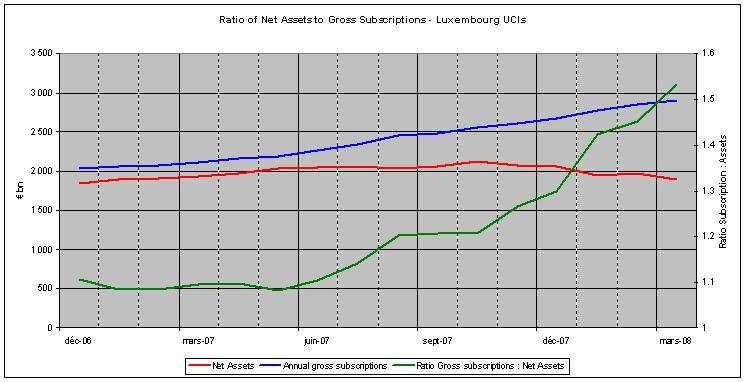

The value of subscriptions and redemptions has increased rapidly over the past two years, from around 150bn per month to a peak value of 300bn at the beginning of 20082 in interest in a variety of swing-pricing mechanisms, equalisation and liquidity management techniques.

The growth in transfers is faster than the increase in fund assets. Fund turnover (annual subscriptions to net assets) has increased from a ratio of 1:1 to a ratio of 1:5.

Even with recent turbulence in the financial markets, the number of funds and transaction volumes has grown. The net asset value (NAV) of funds has flattened and dropped over past half year (although this is mostly due to the rise in the value of the euro). The latest (April 2008) figures for fund creation show strong continued growth in the number of funds:

In one month:Services provided by the TA service providers can be classified as ‘basic' and ‘value-added'. Basic services are the necessary nuts and bolts of the business, handling subscription, redemptions and switches, sending out confirmations and maintaining the register. Value-added services cover areas such as swing pricing, liquidity management, distribution commission calculation and areas that can improve the performance of the fund.

53 funds created

13 funds closed

1,737 new classes

202 new sub-funds

3.8 sub-funds per fund

8.6 classes per sub-fund3

Basic services

The basic services provided cover the reception and processing of TA transactions. Recent years have seen an increasing use of automation, although the fax still remains an important means of communication, especially with smaller distributors and agents.

Fee processing

Increasingly complicated fee structures are being put in place to cope with multi-layer distribution structures. Typically, TA service providers are taking on the whole of the fee processing role, from collecting and distributing entrance fees, to processing and paying trailer fees. TA service providers are increasingly mandated to operate the cash accounts of the fund or to pay these fees, with minimal intervention from the investment manager.

Automation

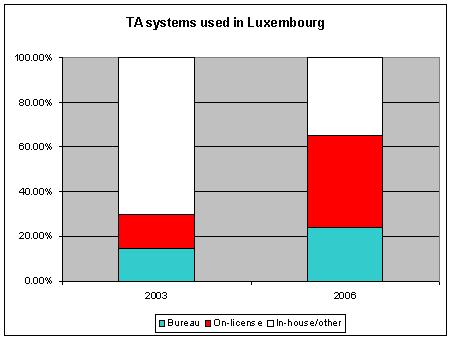

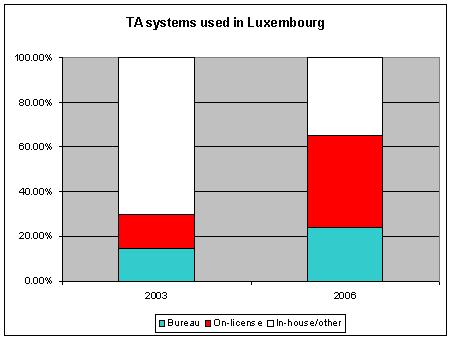

As in other areas, TA processing is becoming more automated - but it lags significantly behind the rest of the fund industry for a number of reasons. In part, these are IT budget constraints linked to the limited fee income generated by TA activities, but they also include the heterogeneity of the fund, clients and transactions. As recently as 2003, most TA providers were using in-house systems for TA processing (see Figure 3).4

The future of automation seems to be connected to distribution platforms, such as Euroclear/Fundsettle, Clearstream/Vestima, Allfunds, DTCC/NSCC and others.

As with systems, the automation of TA interfaces is still less advanced than in other areas of the fund business. At European Fund Administration (EFA), as recently as 2006, only 35 per cent of transactions were processed via straight-through processing (STP), with most others arriving by fax. This is changing rapidly and 54 per cent of transactions in 2007 arrived via STP.5

Anti-money laundering (AML) and ‘know your customer' (KYC) controls

One of the core activities of TA service providers is the opening of register accounts. This has become more complex over recent years, as anti-money laundering (AML) regulations have become more onerous and funds more widely distributed.

TA service providers are expected to know the regulations in all of the markets in which funds are distributed. A funds salesman, having made enormous efforts to pitch a product to, for example, a Dutch pension fund will expect the eventual subscription to be processed with the minimum of paperwork. It is up to the TA service provider to know whether or not this investor is regulated and how this affects the ‘know your customer' (KYC) process.

The trend in this area has been to create specialist departments to handle institutional accounts.

Subscriptions and redemptions in kind

Subscriptions and redemptions in kind is not a new service: almost all fund migrations involve a takeover of investors from one fund to another by a subscription-in-kind process. But these one-off events are often processed manually and without tight deadlines. Recently, with the emergence of exchange-traded funds (ETFs), subscription-in-kind and redemption-in-kind transactions have become more common and subject to the usual processing deadlines. In fact, ETFs generally have much tighter cut-offs than other funds. The number of European ETFs doubled over the last two years, to around 400, and is still growing.6

Investment in ETFs is a two-stage process. Investors purchase shares from the market maker. The market maker later makes an aggregated subscription or redemption to the fund.

After a sale of shares to an investor, the market maker will usually purchase or sell the components of the ETF in order to hedge its exposure to the fund. At the time of the aggregated subscription into the fund, the market maker will make a subscription-in-kind, using the shares purchased.

The regulatory environment

Regulators are getting more involved in the TA process. Just as in the past, financial service companies did not pay too much attention to this part of the production chain, so regulators did not seem to look at it too closely. In recent years, however, we have seen an increasing interest from regulators, in particular in the areas of AML and increased risk monitoring requirements.

Call centres

All major TA service providers provide call centres for investors and distributors. Through incident tracking software and statistical analysis of the issues reported, these centres are increasingly seen as key to improving the processes in TA departments. These systems are linked to risk reporting systems.

Hand in hand with the development of these departments comes the segregation of duties, and a more professional approach to staffing and organisation of the whole area.

Risk reporting

Compliance and risk requirements have driven a new product range from fund administrators - that is, the risk report. Typically, risk reports show details of recent investments: type of investor by share class; residence of shareholders; details of blocked and partially blocked shareholders' accounts; net subscriptions; number of transactions per class, etc.

These reports are generally required by fund boards to monitor the funds. While it is a new area, this can only pick up as regulators require fund boards to track funds more closely. And once a board has started to receive the reports, they find it difficult to justify cancelling the request.

Alternative funds and specialised investment funds (SIFs)

Alternatives come with their own set of special requirements. Complex distribution requirements, the use of side pockets for isolating non-performing investments and cash calls are three areas in which TA service providers have had to add services to meet the demand of these structures.

Specialised investment funds (SIFs), introduced in Luxembourg in 2007, have brought a new set of requirements. In particular, SIFs using a prime broker to execute transactions tend to have a separate cash bank for subscriptions and redemptions. The custodian, who in a traditional variable capital investment company (SICAV, from the French société d'investissement à capital variable) would take on both roles, tends to take a back seat, monitoring the SIF and delegating part of its work to the prime broker. In this set-up, the TA service provider must manage the transfer between the cash bank and the prime broker.

People

All of the trends mentioned above lead to a specialisation of the work being carried out and professionalisation of the industry. In Luxembourg, financial service providers have seen an increase in staff numbers of around 18 per cent over the past 12 months.7. This has led to a tight labour market and a recognition that it is not easy to ramp up production to meet the needs of a new client. Service providers seem either to be taking the approach of recruiting less-experienced staff and putting in place extensive training or simply to be poaching staff from other companies.

Value-added services

In this context, ‘value-added' refers to any service that impacts the return of the fund to investors. Fund managers and promoters are ever inventing increasingly sophisticated ways to protect the return of investors, some of which techniques require TA service providers to integrate additional services into the basic offering. The second half of last year has seen an increase in interest in a variety of swing-pricing mechanisms, equalisation and liquidity management techniques.

Due to the requirements of promoters and investment managers, fund accountants are generally quicker to adapt their systems and procedures to handle these products than are their TA counterparts, who are now playing catch-up with the rest of the industry.

Swing pricing

Swing pricing involves adapting the NAV of subscriptions and redemptions to take account of the transaction costs involved in investing funds received or the costs of liquidating instruments in the portfolio to meet redemption.

Fund managers like swing pricing: in theory, it allows transaction costs linked to subscriptions and redemptions to be charged to investors. Investors are often less keen: they regard swing-pricing mechanisms in the same way as drivers regard traffic fines - that is, as a commendable idea when used on other investors, but not something that they want applied to themselves. Buy-and-hold investors undoubtedly benefit from swing pricing.

Most of the TA service providers now include full and partial single swing pricing in their range of products, although some are still running these calculations on satellite systems (spreadsheets).

Full swing pricing using bid–offer prices of the underlying funds is significantly more complicated, because it requires linking into the accounting system and selecting the underlying pricing method according to the level of net subscriptions.

The larger TA service providers already offer full swing pricing, while the second-tier players are struggling to catch up.

Equalisation

Equalisation involves modifying the price of subscriptions and redemptions to take account of accrued performance fees. The aim is to ensure that all investors pay their fair share of the fees.

Two different methods are widely used: the ‘series of shares' method and the ‘equalisation credit' method.

The ‘series of shares' method is simpler to implement in most systems and perhaps easier to explain to investors. Each time investors subscribe to the fund, a new share class is created. These series of share classes run parallel, with slightly differing NAVs, until the performance fees are paid or crystallised, at which time the series are merged. The main disadvantage of this method is the proliferation of share classes, especially if performance fees are not applicable for a long period of time.

The ‘equalisation credit' method works by creating an account for each investor, which carries the equalisation credit or debit applicable at the subscription date. This amount is adjusted with crystallisation of performance fees or at redemption. This is the preferred method, but requires specific developments.

Like full swinging pricing, equalisation techniques require a link between TA and accounting systems. Larger TA service providers offer this service, while the smaller companies are still catching up with the market.

Pooled assets

Pooling techniques involve the TA service provider in so far as subscription into one fund or asset pool generates subscriptions into other funds or pools. The aim of using pooled assets is to obtain economies of scale in the investment management process.

The TA service provider usually manages pooling structures by means of synthetic subscriptions and redemptions between the funds and underlying investment pools.

It can be argued that many TA service providers would rather not get involved in pooling techniques if they were able to avoid it, but accept it as a necessary evil to concentrate assets and to reduce underlying transaction volumes and costs. The cascade of subscriptions and redemptions through the pool structures generates large volumes of transactions that must be processed in the correct sequence and usually within tight deadlines. Cancellations and amendments pose additional challenges in this environment.

Combined anti-dilution techniques

The next step in value-added services involved combined anti-dilution techniques. All of the techniques mentioned above are widely used, but few TA service providers would claim to offer automated solutions to all of these. A combination of products generally poses additional technical challenges.

Combining pooling with swing pricing makes the work a lot more complicated. Think about the implications: it does not make sense to swing the price of the sub-fund without looking at the underlying pool. It is the added transaction costs of the underlying pool that provide the raison d'être for swinging, so they should be re-priced according to the net amount entering or leaving the pool. This involves flows of information from the top level of the sub-fund down to the pool, and on down to lower levels, if the pool structure is set up with more than a simple dual-level fund pool arrangement. All of this must be done between the cut-off for receipt of orders and the publication of the NAV.

From the point of view of the TA service provider, it seems like a lot of work in a tight deadline to provide a service that is generally disliked by those investors who are caught on the wrong side of the swing - that is, the majority of them.

Furthermore, many TA and accounting systems take a significant time to price the swing on each pool and then on each sub-fund, causing the service provider to bump up against the increasingly tight deadlines for NAV publication. The investment manager may benefit the swing pricing, but then has less time than it would like to reinvest the cash arriving into the fund.

The next generation of integrated TA and accounting systems will presumably address this problem, but, for the time being, there are few funds with pooled asset structures using swing pricing.

Combining partial swing pricing with liquidity management offers greater promise in the short term. Better management of cash and liquid investments can be used to increase the threshold for swing pricing. Swing pricing is only used when transactions exceed the amount of liquidity available from liquidity management services.

Conclusion

The TA service industry is less mature than those of fund accounting or custody, having, until recently, been considered a subsidiary function of these services.

TA service providers can, however, benefit from economies of scale in many areas. TA service providers need flexible systems able to process high-volume STP transactions from distribution platforms alongside fax and mail transactions from smaller distributors and retail clients. But providing the basic services remains a challenge, due to internationalisation and increasing regulation (especially in the areas of AML and KYC), and a trend towards complex distribution structures.

Clients are increasingly asking TA service providers to provide value-added services, such as cash management. TA providers have seen an interest from fund companies in a variety of swing-pricing mechanisms, equalisation and liquidity management techniques. The dual trends combining productivity gain through more automation and scale, and the development of value-added services creates the conditions for the TA business to emerge as a business in its own right. Smaller TA service providers will find it increasingly hard to compete, however, and we can expect them to merge or, perhaps, evolve into specialist boutique operations offering a smaller range of custom services.

References

(1) Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF) (January 2007–June 2008) Newsletter, available online at http://www.cssf.lu/index.php?id=29

(2) Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF) (2008) Luxembourg Fund Industry Profile, available online at http://www.cssf.lu/index.php?id=10

(3) Investment Fund Services Update — May 2008, CSSF & Clearstream.

(4) Pricewaterhouse Coopers (2008) Transfer Agency Systems Survey 2008.

(5) European Fund Administration SA (2008) Annual Report 2007, available online at http://www.efa.lu/EN/who/corporate.html.

(6) European Fund and Asset Management Association (EFAMA) Factbook (2008) available online at http://efama.org

(7) Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF) (2008) Annual Report 2007, available online at http://www.cssf.lu/index.php?id=33

This site, like many others, uses small files called cookies to customize your experience. Cookies appear to be blocked on this browser. Please consider allowing cookies so that you can enjoy more content across globalcustody.net.

How do I enable cookies in my browser?

Internet Explorer

1. Click the Tools button (or press ALT and T on the keyboard), and then click Internet Options.

2. Click the Privacy tab

3. Move the slider away from 'Block all cookies' to a setting you're comfortable with.

Firefox

1. At the top of the Firefox window, click on the Tools menu and select Options...

2. Select the Privacy panel.

3. Set Firefox will: to Use custom settings for history.

4. Make sure Accept cookies from sites is selected.

Safari Browser

1. Click Safari icon in Menu Bar

2. Click Preferences (gear icon)

3. Click Security icon

4. Accept cookies: select Radio button "only from sites I visit"

Chrome

1. Click the menu icon to the right of the address bar (looks like 3 lines)

2. Click Settings

3. Click the "Show advanced settings" tab at the bottom

4. Click the "Content settings..." button in the Privacy section

5. At the top under Cookies make sure it is set to "Allow local data to be set (recommended)"

Opera

1. Click the red O button in the upper left hand corner

2. Select Settings -> Preferences

3. Select the Advanced Tab

4. Select Cookies in the list on the left side

5. Set it to "Accept cookies" or "Accept cookies only from the sites I visit"

6. Click OK

Christophe Lentschat oversees sales, development of new services, marketing and communication at European Fund Administration (EFA). In this capacity, he has a proven record in the acquisition of transfer agent (TA) clients and the creation of new TA services. In particular, he participated in the creation of EFA's TA Bureau service. Prior to joining EFA in 2000, Christophe was a management consultant with Deloitte Luxembourg. Christophe began his career with AXA Investment Managers Germany as a product manager. He holds a Master of Science degree from Sup de Co Reims, France, and a Master of Business Administration degree from Kellogg (Northwestern University), USA–WHU, Germany.

Abstract

Until relatively recently, transfer agent (TA) work was seen as a secondary activity in the fund accounting–custody chain. TA service providers typically earn relatively low fixed annual fees and a small charge per transaction. As such, they have suffered from a lack of investment in specific TA systems. This paper will examine how the most recent changes in product and distribution dynamics are creating new dynamics in the TA industry. It aims to assess the progress obtained in the automation of core TA functions and the existing potential for the development of new added-value TA services. It will attempt to answer the question of whether TA is still a necessary cost of doing business from a fund administrator and custodian perspective, or whether it is becoming a business line in its own right.

Keywords: transfer agent (TA), fund administration, specialised investment funds (SIFs), straight-through processing (STP), equalisation, dilution

Background

The transfer agent (TA) was formerly a function in the corner of the custody or fund administration department. The TA desk's work consisted of calculating trailer fees and other distributor remuneration (usually on a spreadsheet), based on a best-effort estimate of the investors' positions. Until recently, this paper would have made no sense: there were no TA service providers as such. The TA service provider as a separate enterprise or an independently managed profit centre is a new phenomenon, driven by regulation, and by increasing segregation and specialisation of the different elements of the funds services industry.

Most service providers in this industry earn a fee based on the funds assets. This applies to the manager, fund accountant, custodian and distributors. The TA service provider usually has the smallest cut - either a fixed annual fee, or fixed amount per account or transaction. This form of piecework remuneration reflects a persisting view that TA activities are a necessary cost in the distribution process, but with little to add to the performance of the fund. As such, TA service providers are usually mostly out of sight and out of mind of the investment managers and fund promoters - at least, until a large investor goes to them to complain.

In this environment, investment in automated solutions has been slow. Even in the larger service providers, fax and mail transactions are the most common form of transaction. Contrast this with the fund accountants automated processing of portfolio transaction using SWIFT, Bloomberg or proprietary interfaces to prime brokers and it is clear that TA service providers are some way behind the rest of the industry.

Funds are increasingly distributed through other investment vehicles. These ‘assemblers' include funds-of-funds, pension funds, unit-linked products and special purpose vehicles (SPVs). Compared to the traditional retail and institutional clients, these professional fund buyers have demanding requirements for rapid reporting, high levels of connectivity and customised reporting.

The Luxembourg Fund Industry

The Luxembourg fund industry has seen a decade of rapid growth. Recently, the number of funds has been growing at a rate of over 20 per cent per year.1

The value of subscriptions and redemptions has increased rapidly over the past two years, from around 150bn per month to a peak value of 300bn at the beginning of 20082 in interest in a variety of swing-pricing mechanisms, equalisation and liquidity management techniques.

The growth in transfers is faster than the increase in fund assets. Fund turnover (annual subscriptions to net assets) has increased from a ratio of 1:1 to a ratio of 1:5.

Even with recent turbulence in the financial markets, the number of funds and transaction volumes has grown. The net asset value (NAV) of funds has flattened and dropped over past half year (although this is mostly due to the rise in the value of the euro). The latest (April 2008) figures for fund creation show strong continued growth in the number of funds:

In one month:Services provided by the TA service providers can be classified as ‘basic' and ‘value-added'. Basic services are the necessary nuts and bolts of the business, handling subscription, redemptions and switches, sending out confirmations and maintaining the register. Value-added services cover areas such as swing pricing, liquidity management, distribution commission calculation and areas that can improve the performance of the fund.

53 funds created

13 funds closed

1,737 new classes

202 new sub-funds

3.8 sub-funds per fund

8.6 classes per sub-fund3

Basic services

The basic services provided cover the reception and processing of TA transactions. Recent years have seen an increasing use of automation, although the fax still remains an important means of communication, especially with smaller distributors and agents.

Fee processing

Increasingly complicated fee structures are being put in place to cope with multi-layer distribution structures. Typically, TA service providers are taking on the whole of the fee processing role, from collecting and distributing entrance fees, to processing and paying trailer fees. TA service providers are increasingly mandated to operate the cash accounts of the fund or to pay these fees, with minimal intervention from the investment manager.

Automation

As in other areas, TA processing is becoming more automated - but it lags significantly behind the rest of the fund industry for a number of reasons. In part, these are IT budget constraints linked to the limited fee income generated by TA activities, but they also include the heterogeneity of the fund, clients and transactions. As recently as 2003, most TA providers were using in-house systems for TA processing (see Figure 3).4

The future of automation seems to be connected to distribution platforms, such as Euroclear/Fundsettle, Clearstream/Vestima, Allfunds, DTCC/NSCC and others.

As with systems, the automation of TA interfaces is still less advanced than in other areas of the fund business. At European Fund Administration (EFA), as recently as 2006, only 35 per cent of transactions were processed via straight-through processing (STP), with most others arriving by fax. This is changing rapidly and 54 per cent of transactions in 2007 arrived via STP.5

Anti-money laundering (AML) and ‘know your customer' (KYC) controls

One of the core activities of TA service providers is the opening of register accounts. This has become more complex over recent years, as anti-money laundering (AML) regulations have become more onerous and funds more widely distributed.

TA service providers are expected to know the regulations in all of the markets in which funds are distributed. A funds salesman, having made enormous efforts to pitch a product to, for example, a Dutch pension fund will expect the eventual subscription to be processed with the minimum of paperwork. It is up to the TA service provider to know whether or not this investor is regulated and how this affects the ‘know your customer' (KYC) process.

The trend in this area has been to create specialist departments to handle institutional accounts.

Subscriptions and redemptions in kind

Subscriptions and redemptions in kind is not a new service: almost all fund migrations involve a takeover of investors from one fund to another by a subscription-in-kind process. But these one-off events are often processed manually and without tight deadlines. Recently, with the emergence of exchange-traded funds (ETFs), subscription-in-kind and redemption-in-kind transactions have become more common and subject to the usual processing deadlines. In fact, ETFs generally have much tighter cut-offs than other funds. The number of European ETFs doubled over the last two years, to around 400, and is still growing.6

Investment in ETFs is a two-stage process. Investors purchase shares from the market maker. The market maker later makes an aggregated subscription or redemption to the fund.

After a sale of shares to an investor, the market maker will usually purchase or sell the components of the ETF in order to hedge its exposure to the fund. At the time of the aggregated subscription into the fund, the market maker will make a subscription-in-kind, using the shares purchased.

The regulatory environment

Regulators are getting more involved in the TA process. Just as in the past, financial service companies did not pay too much attention to this part of the production chain, so regulators did not seem to look at it too closely. In recent years, however, we have seen an increasing interest from regulators, in particular in the areas of AML and increased risk monitoring requirements.

Call centres

All major TA service providers provide call centres for investors and distributors. Through incident tracking software and statistical analysis of the issues reported, these centres are increasingly seen as key to improving the processes in TA departments. These systems are linked to risk reporting systems.

Hand in hand with the development of these departments comes the segregation of duties, and a more professional approach to staffing and organisation of the whole area.

Risk reporting

Compliance and risk requirements have driven a new product range from fund administrators - that is, the risk report. Typically, risk reports show details of recent investments: type of investor by share class; residence of shareholders; details of blocked and partially blocked shareholders' accounts; net subscriptions; number of transactions per class, etc.

These reports are generally required by fund boards to monitor the funds. While it is a new area, this can only pick up as regulators require fund boards to track funds more closely. And once a board has started to receive the reports, they find it difficult to justify cancelling the request.

Alternative funds and specialised investment funds (SIFs)

Alternatives come with their own set of special requirements. Complex distribution requirements, the use of side pockets for isolating non-performing investments and cash calls are three areas in which TA service providers have had to add services to meet the demand of these structures.

Specialised investment funds (SIFs), introduced in Luxembourg in 2007, have brought a new set of requirements. In particular, SIFs using a prime broker to execute transactions tend to have a separate cash bank for subscriptions and redemptions. The custodian, who in a traditional variable capital investment company (SICAV, from the French société d'investissement à capital variable) would take on both roles, tends to take a back seat, monitoring the SIF and delegating part of its work to the prime broker. In this set-up, the TA service provider must manage the transfer between the cash bank and the prime broker.

People

All of the trends mentioned above lead to a specialisation of the work being carried out and professionalisation of the industry. In Luxembourg, financial service providers have seen an increase in staff numbers of around 18 per cent over the past 12 months.7. This has led to a tight labour market and a recognition that it is not easy to ramp up production to meet the needs of a new client. Service providers seem either to be taking the approach of recruiting less-experienced staff and putting in place extensive training or simply to be poaching staff from other companies.

Value-added services

In this context, ‘value-added' refers to any service that impacts the return of the fund to investors. Fund managers and promoters are ever inventing increasingly sophisticated ways to protect the return of investors, some of which techniques require TA service providers to integrate additional services into the basic offering. The second half of last year has seen an increase in interest in a variety of swing-pricing mechanisms, equalisation and liquidity management techniques.

Due to the requirements of promoters and investment managers, fund accountants are generally quicker to adapt their systems and procedures to handle these products than are their TA counterparts, who are now playing catch-up with the rest of the industry.

Swing pricing

Swing pricing involves adapting the NAV of subscriptions and redemptions to take account of the transaction costs involved in investing funds received or the costs of liquidating instruments in the portfolio to meet redemption.

Fund managers like swing pricing: in theory, it allows transaction costs linked to subscriptions and redemptions to be charged to investors. Investors are often less keen: they regard swing-pricing mechanisms in the same way as drivers regard traffic fines - that is, as a commendable idea when used on other investors, but not something that they want applied to themselves. Buy-and-hold investors undoubtedly benefit from swing pricing.

Most of the TA service providers now include full and partial single swing pricing in their range of products, although some are still running these calculations on satellite systems (spreadsheets).

Full swing pricing using bid–offer prices of the underlying funds is significantly more complicated, because it requires linking into the accounting system and selecting the underlying pricing method according to the level of net subscriptions.

The larger TA service providers already offer full swing pricing, while the second-tier players are struggling to catch up.

Equalisation

Equalisation involves modifying the price of subscriptions and redemptions to take account of accrued performance fees. The aim is to ensure that all investors pay their fair share of the fees.

Two different methods are widely used: the ‘series of shares' method and the ‘equalisation credit' method.

The ‘series of shares' method is simpler to implement in most systems and perhaps easier to explain to investors. Each time investors subscribe to the fund, a new share class is created. These series of share classes run parallel, with slightly differing NAVs, until the performance fees are paid or crystallised, at which time the series are merged. The main disadvantage of this method is the proliferation of share classes, especially if performance fees are not applicable for a long period of time.

The ‘equalisation credit' method works by creating an account for each investor, which carries the equalisation credit or debit applicable at the subscription date. This amount is adjusted with crystallisation of performance fees or at redemption. This is the preferred method, but requires specific developments.

Like full swinging pricing, equalisation techniques require a link between TA and accounting systems. Larger TA service providers offer this service, while the smaller companies are still catching up with the market.

Pooled assets

Pooling techniques involve the TA service provider in so far as subscription into one fund or asset pool generates subscriptions into other funds or pools. The aim of using pooled assets is to obtain economies of scale in the investment management process.

The TA service provider usually manages pooling structures by means of synthetic subscriptions and redemptions between the funds and underlying investment pools.

It can be argued that many TA service providers would rather not get involved in pooling techniques if they were able to avoid it, but accept it as a necessary evil to concentrate assets and to reduce underlying transaction volumes and costs. The cascade of subscriptions and redemptions through the pool structures generates large volumes of transactions that must be processed in the correct sequence and usually within tight deadlines. Cancellations and amendments pose additional challenges in this environment.

Combined anti-dilution techniques

The next step in value-added services involved combined anti-dilution techniques. All of the techniques mentioned above are widely used, but few TA service providers would claim to offer automated solutions to all of these. A combination of products generally poses additional technical challenges.

Combining pooling with swing pricing makes the work a lot more complicated. Think about the implications: it does not make sense to swing the price of the sub-fund without looking at the underlying pool. It is the added transaction costs of the underlying pool that provide the raison d'être for swinging, so they should be re-priced according to the net amount entering or leaving the pool. This involves flows of information from the top level of the sub-fund down to the pool, and on down to lower levels, if the pool structure is set up with more than a simple dual-level fund pool arrangement. All of this must be done between the cut-off for receipt of orders and the publication of the NAV.

From the point of view of the TA service provider, it seems like a lot of work in a tight deadline to provide a service that is generally disliked by those investors who are caught on the wrong side of the swing - that is, the majority of them.

Furthermore, many TA and accounting systems take a significant time to price the swing on each pool and then on each sub-fund, causing the service provider to bump up against the increasingly tight deadlines for NAV publication. The investment manager may benefit the swing pricing, but then has less time than it would like to reinvest the cash arriving into the fund.

The next generation of integrated TA and accounting systems will presumably address this problem, but, for the time being, there are few funds with pooled asset structures using swing pricing.

Combining partial swing pricing with liquidity management offers greater promise in the short term. Better management of cash and liquid investments can be used to increase the threshold for swing pricing. Swing pricing is only used when transactions exceed the amount of liquidity available from liquidity management services.

Conclusion

The TA service industry is less mature than those of fund accounting or custody, having, until recently, been considered a subsidiary function of these services.

TA service providers can, however, benefit from economies of scale in many areas. TA service providers need flexible systems able to process high-volume STP transactions from distribution platforms alongside fax and mail transactions from smaller distributors and retail clients. But providing the basic services remains a challenge, due to internationalisation and increasing regulation (especially in the areas of AML and KYC), and a trend towards complex distribution structures.

Clients are increasingly asking TA service providers to provide value-added services, such as cash management. TA providers have seen an interest from fund companies in a variety of swing-pricing mechanisms, equalisation and liquidity management techniques. The dual trends combining productivity gain through more automation and scale, and the development of value-added services creates the conditions for the TA business to emerge as a business in its own right. Smaller TA service providers will find it increasingly hard to compete, however, and we can expect them to merge or, perhaps, evolve into specialist boutique operations offering a smaller range of custom services.

References

(1) Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF) (January 2007–June 2008) Newsletter, available online at http://www.cssf.lu/index.php?id=29

(2) Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF) (2008) Luxembourg Fund Industry Profile, available online at http://www.cssf.lu/index.php?id=10

(3) Investment Fund Services Update — May 2008, CSSF & Clearstream.

(4) Pricewaterhouse Coopers (2008) Transfer Agency Systems Survey 2008.

(5) European Fund Administration SA (2008) Annual Report 2007, available online at http://www.efa.lu/EN/who/corporate.html.

(6) European Fund and Asset Management Association (EFAMA) Factbook (2008) available online at http://efama.org

(7) Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF) (2008) Annual Report 2007, available online at http://www.cssf.lu/index.php?id=33